The most important condition for the survival of a language is determined by the rate of its circulation among the future generation. The successful inter-generational transmission of a language ensures its continued prevalence and sustenance for at least another half of a century and thus it survives by continuing this chain perpetually. This very fact seems like a foreboding in the case of the Assamese language. A close look at the kind of exposure young children are getting towards the language brings forward many factors that might act as threats towards its survival.

In the last few months, I came across at least three different toddlers, children in the age group of 4-6 years of age, who seemed to be more comfortable speaking in Hindi and English as compared to their own mother tongue, Assamese. Even more interesting was the fact that the parents themselves acknowledged this behaviour saying the kids have gotten used to speaking in these languages and are reluctant to converse in Assamese. According to them it is mainly because the child has a habit of watching cartoons and animation online and wants to speak like their favourite characters. This calls to fore the root cause of this situation being early exposure to screen time which has become unavoidable and virtually a mandatory norm for today’s working parents. While many would rightly argue that this is an escape to an easier parenting method, the realities of modern childcare seem to be shaped by the demands of the economy. Cut throat competition in the rat race, large scale corporate layoffs, toxic work culture and the very fact that childcare itself has faced a year on year inflation of 3-4% has caused work life to bleed into hours that parents of the previous generation could afford to spend in direct contact with their child. This coupled with the growing number of children oriented digital media like gaming sites, YouTube channels and Kids Podcasts, parents find it as an unavoidable option for work life balance.

The threat of the economy towards language does not stop there. The search for greener avenues, getting the most out of one’s potential and personal glory has caused substantial out migration of the young Assamese population. People migrate to other states in search of job options that Assam cannot offer, often with little to no hope of returning to settle in their homeland. The second generation of such parents grow up in an environment bereft of peers that speak their mother tongue. Thus, daily practice of the language during the most interactive hours of the day diminishes. Many a times this also leads to an apathy among children to learn the language questioning its future applicability, replacing it with a larger language just like Hindi replaced many tribal languages in Arunachal Pradesh. In such situations the onus of the child’s love for the language lies solely on the parents, but needless to say, due to limited exposure children from the diaspora are very rarely well versed in all three fields of speaking, reading and writing the language.

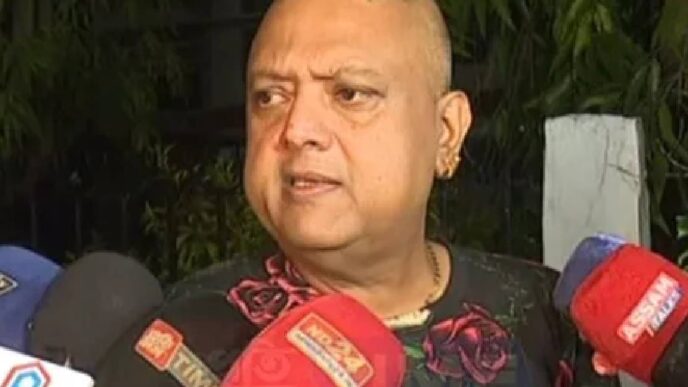

Three years back I met an elder from the Khamyang tribe in their village near Margherita. The man in his early 70s looked visibly upset when he said that they are the last generation who can speak their language fluently and not many from the next generation even understand the language. According to him, one of the main reasons behind this is the intercommunity marriages wherein the parents are unable to converse among themselves in the Khamyang language so it is not transferred to the next generation. The factor of linguistic difference in marital relationships is also coming into play in Assamese families and while there is nothing wrong in choosing one’s own life partner, the consequences of such decisions are undeniably faced by the future of the language, reflected by the children speaking it imperfectly or not at all. Add to this the practice of many schools of the region removing Assamese from their very curriculum every now and then, pushing Hindi as the medium of instruction while masquerading as English medium schools.

Hence, to cater to the demand of entertainment for the children, an eco-system has to be configured to foster production of kids’ programmes, animations, cartoons, comic books etc designed to create an appeal towards the Assamese language. Schools need to make a norm of prescribing Assamese story books and novels as summer vacation assignments to encourage the habit of reading for pleasure. Taking note of the provisions under NEP 2020, this can be further extended to include other regional literature like Bodo, Mising, Karbi, Dimasa etc. Production of educational entertainment programmes under the supervision of the State Education Department to be telecasted on Sundays and holidays in the likes of CIET Tarang during the 90s on Doordarshan can also act as a means to introduce Assam as well as its language and culture to children at a young age.

Most of all, parents must feel obligated to ensure their children get a good hold over their mother tongue. The new age Assamese parents are themselves of a generation that lacked proper induction into Assamese literature. So it is paramount on their part to develop the sense of belonging to their roots and make sure that the next generation is able enough to handle the responsibility of ensuring a language’s healthy survival. In an age where minimalism has replaced expressionist ideas, language has been reduced to its most basic function i.e. conveying information. But it is key to remember that its role is much more than that. A language serves as an identity, a testament of belonging that has evolved through years of practice and has to be in wide usage in order for it to remain so.

The writer is an officer in the Assam Accounts Service