“When myths walk into the present, Assam’s folklores at its best”

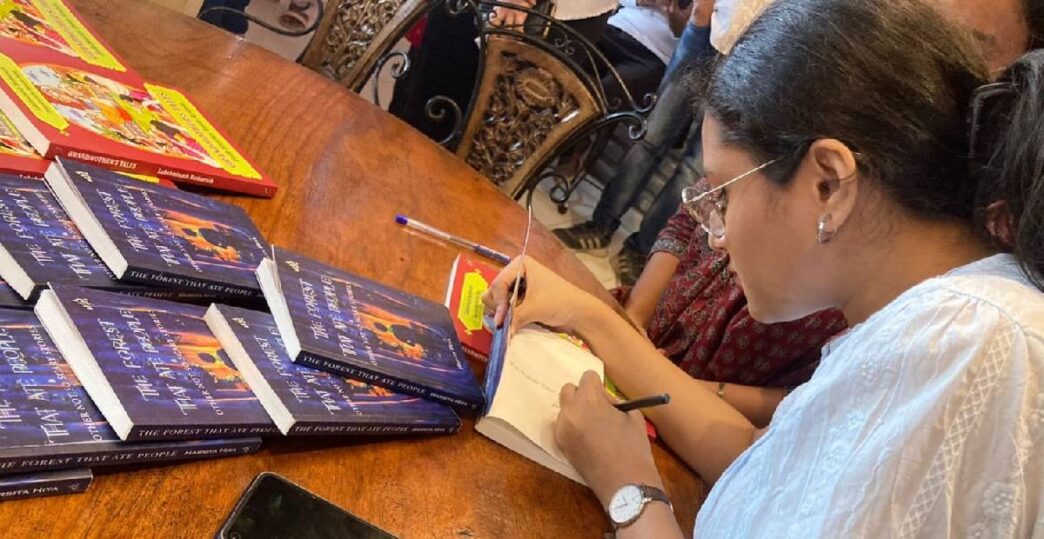

When myths step into the modern world, they don’t fade—they adapt. They change their clothes, borrow our anxieties, and learn to laugh at themselves. This is what debut author Harshita Hiya accomplishes with rare wit and cultural sensitivity in The Forest That Ate People, a collection of ten stories that weave Assamese folklore, everyday humor, and quiet melancholy into something both familiar and startlingly new.

Hiya, a writer and translator from Guwahati, is no stranger to literary circles. Her work has appeared in Words Without Borders, Muse India, and The Little Journal of Northeast India. In 2022, she received the Jibanananda Das Award for translation from Assamese into English by Antonym Magazine during the Kolkata Poetry Confluence. With this debut collection, she steps out of the translator’s shadow and into her own voice—one that is rooted, restless, and gently rebellious.

The Forest That Ate People is not simply a set of stories; it’s a map of how folklore survives. In Hiya’s world, spirits take selfies, stepmothers negotiate second chances, and the weather itself sulks when ignored. Each story functions like a window into Assam’s cultural psyche, while also holding up a mirror to contemporary absurdities. The result is a book that’s part myth, part social comedy, and entirely human.

—

Story 1: Bordoisila Is Nowhere to Be Found

The opening story sets the tone perfectly. In Assamese folklore, Bordoisila is the tempestuous wind-spirit whose brief, dramatic visit each year heralds spring. Hiya takes this familiar myth and turns it inside out. Here, Bordoisila has “vanished”—having apparently gone on a self-discovery trip after reading Eat Pray Love.

Through this conceit, Hiya transforms weather into personality. The seasons themselves—Spree, Mer, Mon, and Winnie—argue and worry like siblings in a chaotic family. The imagery is lush: “Guwahati sleeping like a noisy child,” “the Brahmaputra sighing like a tired parent.” Beneath the humor lies a meditation on disruption and absence. What happens to a place when one of its rhythms stops showing up?

The story’s only slight stumble is a sag in the middle, where repeated “council meetings” between the seasons momentarily dilute the momentum. But Hiya recovers beautifully with the ending, which is cinematic and tender. The first raindrops that fall with Bordoisila’s return feel both literal and emotional—a restoration of balance.

—

Story 2: Swarnalata Das Was Determined to Be Robbed

From the elemental to the absurd, Hiya shifts gears effortlessly. This story introduces us to Mrs. Swarnalata Das, a lonely widow in Bokul Nagar convinced that she’s destined for notoriety—if only someone would rob her. The premise itself is comic gold, and Hiya delivers it with deft timing.

The humor is observational, grounded in the rhythms of small-town life: nosy neighbors, the smell of tea dust, the mild chaos of Assamese domesticity. Swarnalata’s antics—installing elaborate traps, baiting imaginary burglars—play out with escalating ridiculousness, culminating in a “robbery” that turns out to be the work of a cake-stealing monkey.

Yet beneath the laughter lies melancholy. Hiya doesn’t mock her protagonist; she reveals her loneliness. Swarnalata’s craving to be noticed—to have something happen to her—is both ridiculous and deeply human. The story’s irony lands perfectly, and it closes with the light touch of a modern-day Saki: comic, bittersweet, and oddly moving.

—

Story 3: A Carton of Inconvenience

Hiya’s gift for domestic satire shines here. The story revolves around Mrs. Binti Kaur, a woman whose yearly obsession with procuring a prized carton of mangoes spirals into farce. Her niece, Chutney, derails the plan with a fabricated myth about a “beagle god” named Argh/Ugh.

Hiya uses humor to expose superstition, vanity, and the gentle chaos of family life. Every detail—the overripe mangoes, the neighborhood gossip, the exaggerated politeness—rings true. The story’s real triumph lies in its rhythm: dialogue-driven, brisk, and peppered with irony.

While it remains light in tone, there’s a sharp intelligence underneath. Hiya seems to suggest that belief itself—whether in gods, gossip, or mangoes—is the glue of community life, even when it’s absurd.

—

Story 4: Khitik-Khitik

One of the most atmospheric pieces in the collection, Khitik-Khitik marks Hiya’s confident transition into the eerie. The setting is a typical Assamese colony—streetlights flickering, dogs barking, termites gnawing away at furniture. Into this mundane world creeps a haunting sound: khitik-khitik.

Hiya builds tension with restraint. The story moves from children’s whispers to adult disbelief, from rumor to revelation. Her depiction of Munu, a child caught between imagination and terror, is especially strong. Garlic bowls, talismans, and ghostly jewelry become symbols of how children interpret fear.

When the ghostly Rima Saikia finally appears, the effect is more unsettling than overtly scary. Hiya understands that true horror lies in familiarity—in realizing that the supernatural might be hiding behind the ordinary. Khitik-Khitik lingers long after it ends, proving Hiya’s control over tone and pacing.

—

Story 5: The Haunting in Hatigaon

If Khitik-Khitik was about childhood dread, this story explores adult claustrophobia. Set in rainy Guwahati, it follows Simi, whose return home turns a night of thunder into psychological nightmare.

What makes this tale distinctive is its inversion: the haunting isn’t caused by ghosts but by the living. Biju Aunty, Simi’s overbearing landlady, becomes a metaphor for invasive authority and social suffocation. Hiya paints the damp house and flickering bulbs with sensory precision, evoking the feel of a city that never quite dries.

Though a few paragraphs could use tightening, the story’s thematic layering—between the supernatural and the social—elevates it. Hiya reminds us that some hauntings cannot be exorcised because they live next door.

—

Story 6: Crescendo

A tonal shift again, this time into social comedy. Crescendo revolves around Mala Kakati, her tone-deaf tenant Rosy Baidew, and her gossip partner Billy. The result is a delightful portrayal of Assamese housing society life, where sleepless nights, stolen cookies, and festival preparations intertwine.

The humor sparkles, but there’s structure beneath it. Rosy’s off-key singing, initially a nuisance, ends up saving Mala from burglars, turning noise into redemption. Hiya uses irony to great effect—what irritates you today may protect you tomorrow.

Though meandering in spots, the story’s charm lies precisely in its digressions. It captures the pulse of community: nosy, noisy, but ultimately warm.

—

Story 7: Raja’s Homecoming

Meta-narrative meets family farce in this playful story about Raja, a university student returning to Assam for a family picnic. The narrator breaks the fourth wall with jokes and digressions that create a conversational intimacy.

Hiya uses humor to dissect the chaos of Assamese family gatherings—gossiping aunts, chauvinistic uncles, and the endless generational misunderstandings that mark homecomings. Between laughter, a deeper theme emerges: the alienation of returning to a place that should feel like home but doesn’t quite fit anymore.

The brilliance of this piece lies in tone. Hiya manages to be affectionate and critical at once, celebrating her culture while exposing its quirks.

—

Story 8: What Dreams Are Made Of

With this story, Hiya ventures into near-speculative fiction. Nimi, a 15-year-old girl with a bizarre “nightmare superpower,” becomes the unlikely protagonist of a kidnapping story that balances tension with wit.

The setup is light—Nimi’s dreams spill into reality—but Hiya surprises us by turning it into a tale of survival. Even as the stakes rise, Nimi’s banter and teenage awkwardness keep the tone playful. The story’s climax ties her “inconvenient power” back into the narrative with satisfying precision.

There’s a touch of young-adult energy here, but Hiya’s control of pacing ensures it never feels out of place. She knows how to keep magic grounded in the mundane.

—

Story 9: Niyoti Gets Another Chance

Perhaps the collection’s cleverest piece, this story reimagines the legendary stepmother of Tejimola, one of Assam’s most enduring folktales. Niyoti, long condemned as a villain, is denied entry to heaven and sent back to Earth for redemption—or so she thinks.

Hiya’s satire here is razor-sharp. Heaven itself operates like a bureaucratic office; G.K., the celestial gatekeeper, is weary and sardonic. Niyoti’s return to Earth as a modern stepmother becomes a stage for examining how society defines “goodness” in women. The twist—that she’s punished not for cruelty but for losing her edge—turns the moral lesson upside down.

This story encapsulates Hiya’s thematic ambition. She doesn’t just retell myths; she interrogates them. Her humor is feminist, her irony deliberate, and her prose lush with sensory detail—mekhela sadors, chutney jars, and the smell of ginger paste anchoring the fantasy in lived experience.

—

Story 10: The Forest That Ate People

The title story serves as the book’s haunting finale. In a remote village called Kopilipaar, young Dipu decides to test the local legend of Gohbor, “the forest that eats people.” What he finds is not a monster but a mystery that redefines what it means to disappear.

Hiya’s language here is lyrical, her sense of place palpable. The fog, the banyans, the gossiping trees—all feel alive. Nishi, the spectral girl with “eyes like mischief,” is both ghost and metaphor. The forest, it turns out, doesn’t devour—it keeps. The missing villagers haven’t been killed; they’ve chosen to stay.

It’s a deeply symbolic conclusion to the collection. The forest becomes an archive of human emotion—of guilt, love, grief. Hiya’s satire merges with pathos here, suggesting that sometimes, the scariest thing is not being lost but being found by something that understands you too well.

—

Style, Voice, and Themes

Across these ten stories, Hiya demonstrates remarkable tonal flexibility. She can be comic without being flippant, eerie without resorting to cliché. Her prose is descriptive but not overwrought, rich in sensory texture—smells of tea and rain, the chatter of a colony, the whoosh of the Bordoisila wind.

Her use of Assamese culture is neither ornamental nor exoticized. Instead, folklore becomes a living framework for exploring identity, community, and transformation. The mythic and the mundane coexist naturally, reflecting how, in Assam, the line between the two is thin by design.

What distinguishes Hiya from many debut short-story writers is her instinct for structure. Each story has a pulse of its own. Some lean on punchlines (Swarnalata Das Was Determined to Be Robbed), others on emotional resolution (Bordoisila Is Nowhere to Be Found), and a few on ambiguity (The Forest That Ate People). This variation keeps the collection dynamic.

There are, of course, occasional weaknesses. A few stories could benefit from tighter editing; transitions sometimes wobble, and a handful of typos distract momentarily. But these are surface flaws in what is otherwise a remarkably assured debut.

Thematically, Hiya’s world is populated by lonely women, curious children, talkative neighbors, and restless spirits—all searching for connection. Whether it’s Swarnalata’s yearning to be robbed or Bordoisila’s impulse to wander, each story examines absence as a form of longing.

—

Conclusion: A Promising Debut from the Northeast

The Forest That Ate People stands as one of the most inventive contemporary story collections from Northeast India in recent years. Harshita Hiya writes with humor, empathy, and a keen sense of cultural inheritance. Her Assam is not a postcard landscape—it’s alive, contradictory, mischievous, and deeply human.

By reimagining folktales like Bordoisila and Tejimola, and embedding them within modern sensibilities, Hiya proves that folklore is not static—it evolves as long as someone dares to retell it. Each story in this collection feels like a small act of reclamation: of women’s voices, of local mythologies, of laughter amid loss.

If a few stories falter in pacing, the collection as a whole remains remarkably cohesive in tone and theme. Hiya’s talent lies in her ability to balance reverence with rebellion. She neither glorifies nor dismisses her cultural roots; she plays with them, argues with them, and ultimately lets them breathe.

In the end, The Forest That Ate People does what good folklore always does—it whispers truths beneath its laughter.

★★★★☆ (4/5)

A captivating, intelligent debut that redefines how Assamese folklore can speak to the modern world.

- Puja Mahanta

A word from the author

Like most fiction, every story in The Forest That Ate People is real life filtered through a torrent of what ifs. For instance, what if the terrible-awful of dealing with pesky landlords was turned into a cliche-riddled horror story? What if Bordoisila, the legendary wind spirit every Assamese is familiar with, gets bitten by the travel bug and ends up skipping her annual visit? This ‘what if’ filter was as much an inspiration for Raja’s Homecoming— one of my oldest stories featuring an interactive, motormouth narrator which I wrote back in 2016— as it was for the titular story which draws from my personal navigation of grief. Choosing Assam as a backdrop for all the stories was the most natural decision. The places and people that defined my childhood were bound to roam freely in my imagination, for not only did they hold the key to it, they had pretty much built it from the ground up. The fact that I barely got to see my lived environment represented in the English books I grew up reading was certainly another strong motivation here. I can’t claim that the short stories in TFTAP are topical in the general sense of the term. They weren’t written to tick any boxes, which perhaps becomes evident in the lack of any premeditated thematic coherence. However, I can vouch that they are coherent in their earnestness, their faithfulness to the journeys of their protagonists as well as the spirit of storytelling.