Exclusive | Northeast Scoop

The Assam government’s decision to proceed with a foundation stone–laying ceremony for a new structure at Rangmahal in North Guwahati on January 11 has triggered a serious legal and institutional confrontation between the BJP government and the state’s legal fraternity.

At the centre of the dispute is a clear statutory bar under the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971, which lawyers say makes the government’s attempt to shift the Gauhati High Court illegal.

The Gauhati High Court Bar Association has announced a complete boycott of the January 11 ceremony, calling it a direct violation of parliamentary law, judicial independence, and the institutional dignity of the High Court. The decision was taken at an emergent extraordinary general meeting on January 6, where there was near-unanimous opposition to the government’s move.

Since January 8, advocates have been sitting on a daily hunger strike from 10 am to 4 pm in front of the old Gauhati High Court building, urging unity within the Bar and demanding protection of the High Court’s status and location.

The law that blocks the move

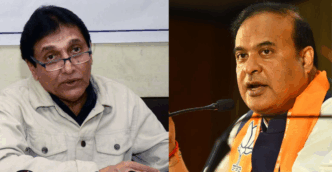

Senior advocate Kamal Narayan Choudhary, speaking exclusively to Northeast Scoop, said the government’s plan violates Section 31 of the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971.

“The Act clearly states that the principal seat of the High Court shall be located at the place where it existed on the appointed day,” he said. The appointed day refers to 1972, when the Act came into force.

“There is a parliamentary prescription that the principal seat of the High Court would be situated at the present location. Unless that law is amended, how can an executive order or even a decision on the administrative side shift the High Court from its present location?”

According to the Bar, this statutory mandate cannot be overridden by a state government decision. Any attempt to relocate the High Court without amending the Act would therefore be unconstitutional.

The Bar Association plans to base its legal challenge primarily on this provision. “There are legal flaws in the decision-making process,” Choudhary said. The Association is preparing to move either the Supreme Court or the High Court after reopening, around January 19 or 20.

Why January 11 matters

The government insists on proceeding with the foundation stone ceremony at Rangmahal on January 11, even though no construction contract has been awarded.

“Mere laying of a foundation stone is nothing. The contract has not been awarded. The land will remain with the Assam government. They can still do many things with it later,” Choudhary said. “But the political meaning of the ceremony is huge.”

He said the government’s refusal to postpone or cancel the event shows its unwillingness to engage.

“On one side, the government is adamant. On the other side, lawyers are protesting and sitting on hunger strike. This sends a very clear message,” he said. “Everybody knows this government listens to no one. But we cannot give up.”

What lawyers say the project is really about

According to Choudhary, the Rangmahal project is not primarily about building court infrastructure.

“The proposed structure is not about courts. It is about a large convention centre. There will be a lot of parking areas. It is about security. When the Prime Minister and others visit the state, they can stay there,” he said.

He said the land in question lies in the former Brahmaputra Ashoka Hotel zone, which the government prefers because of its size and parking capacity.

“For the BJP government, the High Court is not important. For them, the convention centre is more important,” he alleged.

Existing High Court can be expanded

The government has projected the current High Court building as inadequate. Lawyers dispute this.

The High Court was established in 1948, and its annex building was inaugurated in 2014, just ten years ago. According to Choudhary, the structure was built on a seven-storey foundation.

“Vertically, at least three more floors can be added. If they raise three more floors, we can have at least 15 courtrooms,” he said. There is also land behind the present premises that can be used for expansion.

“Such shortcomings can always be sorted out. It is not such a type of shortcoming that it cannot be addressed unless the premises is shifted,” he said.

Alleged betrayal by the Chief Minister

Choudhary said the Bar had been misled. During a meeting with the Chief Minister in 2024, lawyers were told that no land would be acquired until after the new bridge over the Brahmaputra was completed and both sides jointly assessed the distance and travel time to North Guwahati.

“At that time, we thought there was no scope for protest,” he said. “But see how he lied to us. He had already acquired the land.”

This, lawyers say, destroyed trust and forced them to escalate the protest.

Overwhelming opposition inside the Bar

The Bar Association says 1,164 lawyers oppose shifting the High Court, while only 154 support it, mostly government advocates. There are around 300 government advocates in total.

The pro-government group is led by Devajit Saikia.

The Association argues that this shows the legal community overwhelmingly rejects the move.

Access to justice at stake

Lawyers fear that shifting the High Court to North Guwahati will create serious access problems for litigants and lawyers, particularly those travelling from distant districts. They also argue that abandoning the historic High Court site without exhausting all expansion options disrespects the institution’s legacy.

By staging their hunger strike in front of the old High Court building, advocates are emphasising its role in Assam’s legal history and constitutional life.

The protest has remained peaceful and disciplined. Apart from boycotting the January 11 foundation stone ceremony, no disruption of court work has been called.

With the government refusing to pause and the Bar preparing legal action under a central parliamentary law, the confrontation is now moving towards the courts.

For the lawyers sitting on hunger strike each day, the issue is no longer just about a building — it is about whether an elected government can override a law passed by Parliament and relocate a constitutional institution by executive will.