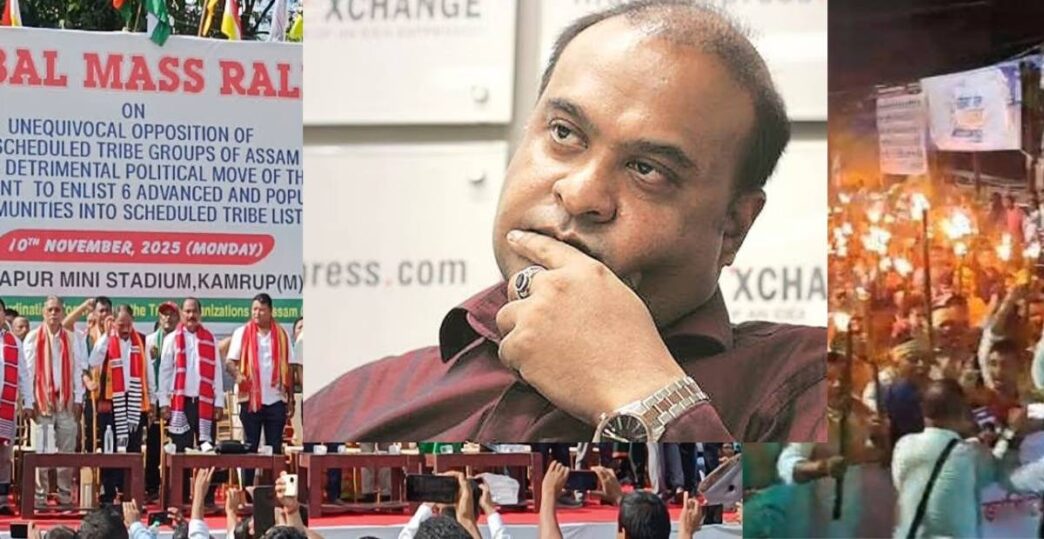

The chants at Sonapur Mini Stadium on November 10 weren’t festive slogans but the roar of anxiety. From Assam’s hills and plains, thousands poured in for a massive rally organized by the Coordination Committee of Tribal Organisations of Assam (CCTOA). Their demand was simple — protect what’s left of their hard-won rights. Their fear — the state’s plan to grant Scheduled Tribe (ST) status to six more communities: Moran, Matak (Muttock), Ahom, Chutia, Koch-Rajbongshi, and Adivasi (tea tribes).

The message from the stage was unambiguous: Assam’s existing 14 Scheduled Tribes — about 38.84 lakh people or 12.45% of the state’s population — feel cornered. They say adding nearly two crore new entrants, almost 55% of the population, will swamp the benefits meant for the most marginalized: reserved seats, government jobs, and educational opportunities.

“We’ve built this protection step by step,” said Aditya Khakhlari, a CCTOA leader. “After 78 years of Independence, it’s time to stop widening the list. These gains cannot be diluted.”

The Fear of Being Pushed Out

Tankeswar Rabha, Chief Executive Member of the Rabha Hasong Autonomous Council, minced no words. “The six groups are already economically stronger,” he told Northeast Scoop. “Ahoms ruled kingdoms, Koch-Rajbongshis had dynasties. They have political clout. What happens to smaller tribes like ours if they’re added? We’ll be marginalized further.”

Rabha described the crisis as “promotion versus demotion.” In his words, “We are defending our rights. The government must listen.”

The fear isn’t new. In 1996, when Koch-Rajbongshis were briefly granted ST status, they secured 33 of 42 medical seats and 17 of 21 engineering seats reserved for tribals. Protests forced a rollback — a memory that still fuels apprehension.

Dr. Subhash Rabha of the All Rabha Students’ Union echoed that sentiment: “ST status is for those with socio-economic disadvantage and primitive traits. The claimants are populous and politically powerful. If all are added, our rights vanish.”

The Demand for Inclusion

But the other side insists the exclusion has gone on too long.

Babul Paik, President of the Udalguri unit of the All Adivasi Students’ Association of Assam (AASAA), countered: “We’ve pursued ST status since 1999. This is a constitutional right. In other states, Adivasis already have it. Assam delayed. If ignored, voters will decide in 2026.”

For these six communities, the fight is about recognition and dignity. The tea tribes alone — descendants of labourers brought from central India — make up around 70 lakh people, living with low literacy and poor wages. Ahoms, Morans, and Mataks, meanwhile, invoke their historical role in shaping Assam’s identity.

Basanta Gogoi, President of the All Tai Ahom Students’ Union (AATASU), accused a BJP minister of “funding the Sonapur rally to divide communities.” He warned Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma to act before tensions spiral.

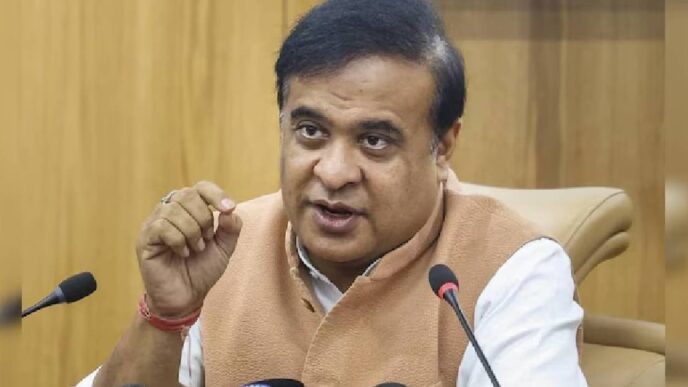

BJP’s Tightrope Walk

Caught between two raging fronts, the BJP faces a dangerous balancing act.

The party has promised ST status to these six groups since 2014 — a key campaign plank repeated in Modi’s Kokrajhar speech and in the 2019 ST Amendment Bill that never passed Parliament. Now, with the Group of Ministers set to submit its report on November 25, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

The Registrar General of India has already rejected the proposal four times since 1981, citing the absence of “primitive traits” and socio-economic disadvantage. But politically, the pressure to deliver is immense — both from powerful community lobbies and from within the BJP’s own ranks.

So, who’s right? Who’s wrong?

The 14 existing STs — 38 lakh people fighting to preserve limited quotas?

Or the two crore aspirational groups demanding long-denied recognition?

For now, Assam’s tribal faultline is widening — and the BJP stands in the middle, trying to hear both sides but inevitably risking losing one.

As November 25 nears, the real question isn’t just who gets ST status — but whose voice the government decides matters more.